Eddi Cohen, R.N., B.S., MICN, CCRN, CFRN (ret), MRCNA

Clinical Nurse Consultant, Sydney Australia

What dentists should know about nursing's dirty secret and oral care Part I

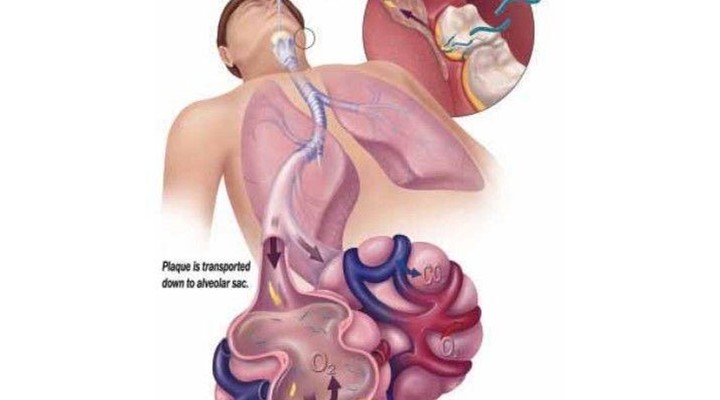

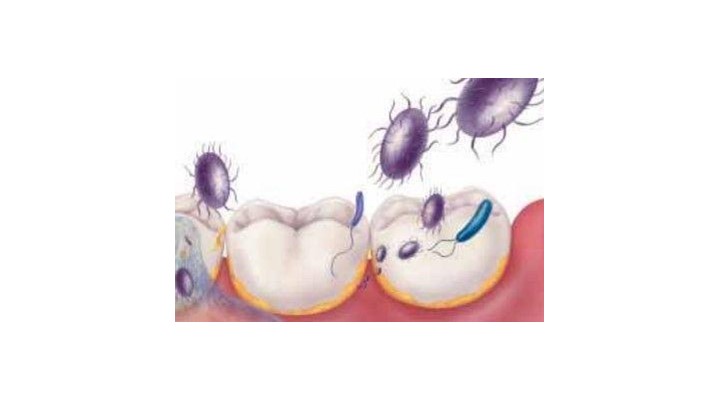

Poor oral health and periodontal disease is known to increase risks for respiratory infections, diabetes, stroke and cardiovascular disease1. Despite this awareness, poor oral hygiene continues to play a significant role in pneumonia rates among nursing home residents, particularly those at risk for aspiration.

Aspiration pneumonia, which is typically caused by anaerobic organisms (commonly S. aureus, P. aeruginosa or one of the enteric species) arises from the gingival crevice and seen in both the community and institutionalised settings. Pneumonia develops when pathogens are aspirated from the oropharyngeal cavity and other sites (GI tract, sinuses) into the lower airway.

Increased risks for aspiration pneumonia occur when a sequence of periodontal disease, dental decay and poor oral hygiene is compounded by the presence of dysphagia, feeding problems and poor functional status all of which are found in vulnerable dependent persons.1, 2, 32 But modifiable risks of aspiration pneumonia do exist; these include implementation of standardised evidenced based practices (EBP) in oral hygiene, routine oral assessment, mechanical cleansing to reduce biofilm and strict adherence to aspiration precaution protocols.1,2,32 Consequently, an urgent need exists to improve the state of oral care for vulnerable and dependent persons, particularly those who are dentate.

Current state of oral health and care

Pamela Stein writing in the AJN noted that many institutionalised persons cannot perform their own oral care with studies in the UK reporting that 72-84% of nursing home residents had difficulty in brushing their own teeth and up to 94% found it difficult to clean their own dentures. Similar studies support the opinion that oral hygiene in long term care facilities are poorly constructed and controlled, not standardised or deemed to be of a priority by staff.

Without question the level of oral care provided by staff is a key indicator on the quality of care that is delivered in general; the appearance of dry cracked lips, coated tongue, vegetation on teeth and halitosis indicate a lack of oral care and flagrant disregard for the well-being and comfort of the dependent person. Conversely, good and effective oral care reflects a culture of caring and compassion; and as nursing has a ‘duty of care’ to provide comfort and maintain the health and well-being of those in their charge, poor oral hygiene is the antithesis of the nursing profession.

A study of 71 edentulous elderly persons in Japan assessed ‘tongue coating’ as a predictor or risk indicator in the development of aspiration pneumonia; the number of elderly patients developing aspiration pneumonia was larger in patients with a poor TPI score (tongue plaque index) than those with better or good TPI scores. As a result “tongue coating was associated with the number of viable salivary bacterial cells and development of aspiration pneumonia in dentate persons”.

Nursing Home executives have conceded that oral hygiene in their facilities are lacking and rated as only “fair to poor” and oral hygiene

in many cases, is underrated by staff as to its influence on overall patient health, well-being and nutritional status. 6,7 In studies of nursing homes in the US and Australia, the ‘so-called’ barriers to providing good oral care included the lack of assigned personnel to perform oral care, resident noncompliance with care and choice of oral care itself.

Whilst providing oral care may be a challenge in the elderly and disabled, failure can have dire consequences as poor oral care can contribute to serious illness and possibly, death. Terpenning and associates in 2001 wrote of the link between pathogenic oral bacteria and aspiration pneumonia with a subsequent study in Japan showing that poor oral hygiene in nursing homes significantly increased the risk of pneumonia and febrile days.

With aspiration pneumonia accounting for 13% to 48% of all infections in nursing homes, growing evidence supports the causal links between oral hygiene, mechanical cleansing, aspiration risks and development of pneumonia in ‘high risk’ patient populations. However this awareness is not new with literature going back to the 1980’s documenting links between poor oral hygiene and illness.

The importance of oral care as a preventative measure in maintaining systemic health has been so compelling that in 2003 the CDC and HICPAC released “Guidelines for Preventing Health Care Associated Pneumonia”.

This stated that healthcare facilities must “...develop and implement a comprehensive oral-hygiene program (that might include use of an antiseptic agent) for patients in acute-care settings or residents in long-term care facilities who are at risk for healthcare associated pneumonia (II)*.”

In Australia, The Commonwealth Residential Aged Care Standard set out accreditation requirements for residential care providers. Standard 2.15 Oral and Dental Care requires that “resident’s oral and dental health is maintained”34. Under this Act, nursing home providers are required to:

- Meet specific standards on oral and dental care (outcome 2.15)

- Refer residents to appropriate health specialists in accordance with the residents’ needs and preferences, including dentists.

- Demonstrate that residents’ oral and dental health is maintained through documentation

According to the ADA in 2004, despite the existence of these standards there has been little enforcement and no strong adherence due to insufficient knowledge regarding oral health, oral care and low priority by staff.

Literature Review: Oral Hygiene and Pneumonia

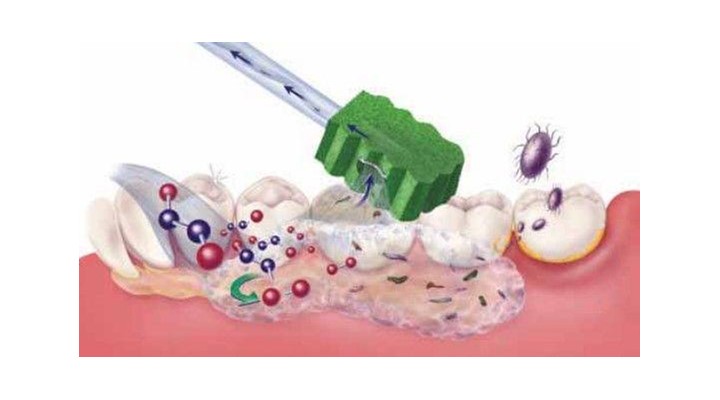

In JADA, 2006 Scannapieco noted that the increased oral colonisation and dental plaque found in intubated ICU patients served as a major reservoir of infection by respiratory pathogens and that “oral bacteria and oral hygiene had a role in the development of pneumonia in non-ambulatory patients”. He and others have concluded that “oral interventions aimed at controlling or reducing oral biofilms can reduce the

risk of pneumonia in high risk populations” and that the “institution of rigorous oral hygiene regimens for hospitalised patients and long term

care residents may reduce the risk of developing pneumonia”.

Limeback in 1988 previously noted that poor oral hygiene had a negative impact on the overall health of nursing home residents with “poor oral hygiene increasing exposure of pathogenic micro-organisms found in the mouth and together with a reducedhost defence mechanism increased the incidence of systemic disease”.

Supporting these findings Abe, et al in 2005 wrote that a greater number of patients in a Japanese nursing home who developed pneumonia (among dentate patients) had correspondinglypoor oral hygiene scores.

It was Rosenblum in 2010 that put a statistical face to oral hygiene and associated poor patient outcomes by concluding that “mechanical oral hygiene decreases the risk of dying as a result of pneumonia and has a clinically relevant preventive effect in dependent elderly”. He determined that daily oral hygiene reduces the occurrence of health-care acquired pneumonia and lower respiratory tract infections and that “mechanical oral hygiene practices may in fact, prevent 1 in 10 elderly nursing home residents from acquiring a health care associated pneumonia”.

Nursing’s ‘Dirty Secret’ about oral hygiene

The bridge between oral health, pneumonia risks and patient outcomes is the role nursing has in providing diligent evidence – based oral care; regrettably this also the very task that nurse’s and others often view as “nonessential” or given as a low priority in the pecking order of care.

Patricia Coleman wrote in 2004 “nurses have a professional duty to ensure basic oral health care for patients” and that oral care, like other

‘basic’ nursing procedures of bathing, toileting and feeding is essential to the care that nurses and assistants provide to those who can’t care for themselves”.18,29 Whilst professional dental visits and daily conscientious oral hygiene reduces oral pathogens, it is nursing or other carers who provide the essential day to day oral care vital to reducing build-up and oral biofilm, the reservoir for respiratory

organisms.

Though nursing literature abounds with support for mouth moisture, adequate salivary flow and control of plaque formation to preserve oral health it is often a poorly informed and motivated front line team that determines whether recommended interventions are properly performed and applied. But despite ongoing evidence showing a relationship between oral health and systemic illnesses, oral hygiene care continues to remain unchanged and for the most part, unchallenged particularly in long term care facilities.

What does this mean in the “real world?”

Nurses must focus their efforts on maintaining mouth cleanliness, preventing infection, moisturising the oral cavity and maintaining mucosal

integrity. Well performed oral care may prevent or relieve oral discomfort, reduce inflammation of the oral mucosa and should aid in improving nutritional status, speech and patient outcomes particularly for those with wounds, ostomy or incontinence.

Unfortunately many facilities for a number of ‘reasons’ (lack of education, low priority, financial), do not keep on hand the correct ‘tools’ and

equipment for providing oral care; staff instead use an “ad hoc” approach which includes the use of unapprovedand clinically unsupported implements for care.

In many cases, what passes as oral ‘hygiene’ is not evidenced-based care but rather ‘tradition based’ practices. Even in the face of mounting evidence and clinical guidelines, a large number of facilities both acute and long-term remain entrenched in their use of outmoded, unsubstantiated and potentially harmful oral care practices; these include the use of:

- Jumbo cotton swabs dipped in water with / without sodium bicarbonate

- ‘Swabs’ instead of toothbrushes in dentate persons

- Sponges on forceps / wrapped around tongue depressors or fingers

- ‘Mouthwashes’ in lieu of brushing often applied with cotton swabs or gauze pads

- Lemon and Glycerin Swabs

This “real world” practice of institutionalised neglect was reported by Stein, et al in June 2009 in a case study entitled “Asphyxia Caused by

Inspissated Oral and Nasopharyngeal Secretions”. Stein documented the case of a severely disabled man who received such ‘poor’ and negligent oral care that a build-up of thickened oral and nasopharyngeal secretions blocked his airways causing death from asphyxiation.

The authors cited a pattern of neglect in LTC facilities in which “only 16% of nursing home residents receive any oral care, with an average toothbrushing time per resident of only 16.2 seconds, a period that is woefully inadequate.”

Reported barriers to care and explanations for the lack of oral hygiene by ‘nursing’ staff (R.N and nursing aides) included:

- Performing oral care on a fully dependent patient requires time and patience; elements which are in short supply when patient acuity increases and nursing staff decreases.

- Administering medications, monitoring patients, educating patients and family, and conferring with other professionals take up a lot of nursing time.

- Patient’s combative behaviour makes oral care even harder to provide and therefore not considered a ‘priority’.

Carer’s admitted that when time was short and other tasks were pressing, oral care was the “first to go”. Others cited that oral care was too difficult to perform, disgusting, distasteful and there was fear in cleaning someone else’s mouth, particularly if they were resistant to care. Not surprisingly, one of the greatest barriers in providing oral care was the lack of readily available and appropriate supplies or equipment.

Compliance in Oral Care: the ultimate influence on outcomes and practice

Whilst the above report might be viewed as an extreme case, neglect and poor oral care remains a significant issue in nursing. The hidden and often unaccounted issue of staff ‘compliance’ in performing daily oral hygiene is the cornerstone of success or failure; if only a portion of staff “buy in” to the changes in care and do not fully embrace them, patient outcomes will be less than desired.

Adding to the mix of staffing and performance pressures, staff receive little to no training in oral hygiene, use “improvised” oral care practices instead of standardised policies and procedures and do not perform daily oral assessments to document changes in oral integrity and dysfunction. Most telling was Aiken in 2001 who exposed various inconsistencies in care when 43,000 nurses in 5 countries were polled on what nursing procedures were not completed due to ‘staffing shortages’; included in their responses 20% admitted to not performing oral care and 31% basic skin care.

Consequently in order to promote an evidenced based oral care model in acute and long term care settings, focus must include oral hygiene education for all staff, implementation and enforcement of standardised oral care procedures and most importantly the immediate removal of any clinically unapproved or ad hoc “tools” of care.

Part II of this series (in the next issue of Australasian Dentist) will follow on looking at solutions in optimising oral care for dependent persons.

As a Clinical Nurse Consultant, Eddi Cohen specialises in the prevention of healthcareacquired infections and its relation to clinical nursing practices in hygiene care; for over 18 years she has been a popular and frequently requested lecturer in conferences and workshops throughout Australia, Singapore and New Zealand where she presents the concept of ‘‘interventional patient hygiene”, a process designed to reduce occurrences of HAI’s (Healthcare Acquired Infections) and HASI (Healthcare aquired skin injuries) in high risk patient populations such as the critically ill and institutionalised dependent persons.

A graduate of Boston University, Eddi Cohen actively works to change nursing practices from tradition – based to evidenced – based protocols promoting excellence in nursing care. Author, lecturer and clinical expert in skin and oral care she focuses on the prevention in the occurrences of pneumonia, skin breakdown, pressure ulcers and surgical site infections by driving changes in policy and procedures.

A critical care clinician, educator and product specialist for over 35 years, Eddi divides her time between Sydney and Los Angeles, California and is Medical Director of Mobile Medical Systems International.

What dentists should know about nursing’s dirty secret and oral care Part II

In Part I of “What Dentists Should Know about Nursing’s Dirty Secret and Oral Care”, we discussed the types of inappropriate oral hygiene and neglect found in healthcare settings, why staff are resistant to performing oral care, their persistence in using improper “oral cleaning” tools and the causal relationship between poor oral care, biofilm and respiratory infections. In Part II, we now look at solutions to optimising care, how to overcome resistance by nursing staff in performing oral hygiene and what is being done to promote evidenced based practices particularly in nursing homes.

Whilst studies have shed light on the level of poor oral care in nursing homes across the globe, the same can be said for Australian facilities. Hopcraft (Gerodontology Nov 2010) cited that “poor oral hygiene and the presence of significant plaque and calculus” are common findings in Victorian nursing homes; as such “addressing the healthcare needs of residents require improved training for carers and better access

to dental services”.

Solutions to optimising care

Demands for good oral hygiene is increased by an aging population who are dentate, have pre-existing periodontal disease and history of oral neglect. Effective delivery of good oral care whilst not highly technical takes education and training to raise awareness, promote clinical competency, knowledge and theory.

Deficits in the knowledge by personnel in dental and oral hygiene are often cited as one of the causes for lack of care; but implementation of oral hygiene education programmes for nursing home staff have been shown to be effective in improving the oral health of residents.25 Essential elements for successful training programmes include:

- Provision of oral hygiene supplies

- Provisions of forms for daily documentation of oral care

- Education on oral diseases

- Instruction on oral assessment

- Education on the importance of oral care

- Training conducted in small groups

- Hands-on-training for delivery of oral care, particularly for care-resistant patients

In 2009 the Department of Health and Aging rolled out a government funded training program called the Australian Better Oral Health in Residential Care. The training modules aim to provide an increased awareness of oral hygiene issues for the staff in daily contact with residents. “Using a train-the-trainer approach, the intention is to train up to two registered nurses or dedicated trainers in each Australian Government funded residential aged care facility, multi-purpose service and Indigenous flexible residential aged care service as trainers, so that they in turn, can train and support aged care workers in ensuring residents’ daily oral hygiene is maintained. In addition, registered nurses will be provided with the tools to enable them to undertake oral health assessments and oral health care planning”.

It should be noted that successful oral hygiene education / training programmes are dependent on good attendance and follow-through. A 2007 study showed no significant improvement in oral health in 14 long term care facilities when attendance at training sessions was poor (15%).22 Given the government funded program is limited to selected staff members to act as “trainers” for their own facilities, the ability of those individuals to teach and motivate would have to be monitored with administrators enforcing a 100% attendance by all staff. This should be followed by on-going surveillance and monitoring of oral care practices throughout the facility.

A promising and ambitious program aimed on educating staff about oral health and dealing with special needs clients, the ABOHRC is directed at Australian government funded facilities only. Its overall affect in changing oral care practices at the end user level is yet

to be determined but highly anticipated.

Oral Hygiene: Recommended Approaches and Tools

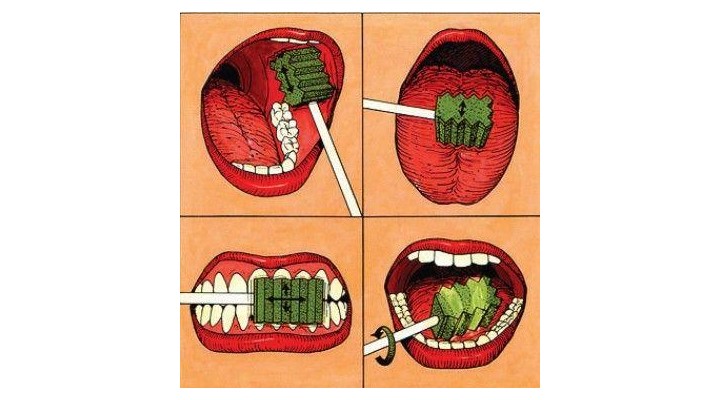

In nursing there are four components to providing evidenced based oral care:

- Routine oral health assessment using a standardised tool, minimum of once per day and on admission

- Oral cleansing using appropriate agents to maintain mucosal integrity and pH

- Debridement of oral structures (including the teeth, tongue, buccal cavities and pallet) using appropriate implements to reduce presence of dental plaque and debris

- Moisturising of the oral cavity and its’ structures particularly in those with significant xerostomia

The frequency in which oral care is provided throughout the day is based on a systematic oral assessment ‘score’ used to benchmark or track changes in oral integrity. The use of OHAT scoring has been adopted in many centres in Australia but a variety of modified oral health assessment tools are currently in use.

The author’s preference is for an oral screening tool which guides oral care by assigning a rating or numerical value to any observed dysfunction of the lips, gingiva / oral mucosa, tongue, teeth and saliva. Scores are ranked as “no observed dysfunction”, “moderate” or “severe” oral dysfunction; appropriate oral care interventions are then recommended for each ranking to guide nursing personal in developing a relevant plan of care. 30 For example, a ‘moderate to severe’ dysfunction score would indicate that more frequent and diligent oral care should be provided.

The type and frequency of care is then more fittingly based on the level of dysfunction and adjusted to the persons’ oral health needs as required.

Tools of the trade: brushing, cleansing and moisturising

Oral care takes time, diligence and technique all of which are issues within the nursing culture; and whilst tooth brushing is the most effective means for removing dental plaque, there are also those persons who cannot use them due to physical (i.e. low platelets) or emotional reasons (i.e. “mouth phobic”, uncooperative).

Improved oral care practices by nursing staff can be achieved through training and use of standardised, clinically proven implements and “adjuncts” designed to enhance oral care. Newer tools have come on to the market which can make it easier for carers and improve delivery of oral care which should be considered when recommending products.

Mechanical debridement / brushing:

- An ultra soft, small headed or paediatric toothbrush is preferred; if tolerated, electric toothbrush is acceptable but infection control issues exist, particularly if “handles” are shared.

- A flexible three-headed toothbrush (Surround® Toothbrush) makes it easier and quicker to brush another’s teeth; excellent for those with short tolerance due to behavioural issues as all surfaces are brushed simultaneously in a shorter period of time; easier for caregivers to use over a modified toothbrush “bent” at a 45 degree angle to improve mouth access. (concerns exist when carer’s attempt to bend toothbrushes not designed for such manipulation)

- For those with high risk for aspiration during oral care, a suction toothbrush is preferred

Toothbrush alternatives / adjuncts to oral care:

Foam oral swabs aka Toothette® Swabs stimulate and cleanse the oral mucosa, buccal areas, gum line, temporal-mandibular ridges, tongue, hard pallet and lips.

- Oral swabs don’t replace toothbrushes in those who are dentate or can tolerate brushing

- Oral swabs are recommended for inbetween AM and PM tooth brushing and used every 2-4 hours for those with moderate to severe oral dysfunction.

- Frequent swabbing stimulates and moisturises the mucosal tissue to minimise oral dysfunction.

- Foam swabs impregnated with sodium bicarbonate avoids under or overdosing with incorrectly prepared sodium bicarbonate solutions mixed / stored at the bedside; aids in cleansing, lubricating, preventing crusting and gently removing debris between brushing.

- Foam swabs used with 1.5% hydrogen peroxide and sodium bicarb increases effectiveness of the debriding action and helps thin ropey, thickened secretions found in those with severe oral dysfunction and aids in removing oral secretions.3,30

- Plain foam swabs are preferable over “jumbo swabs” or gloved fingers to apply mouth gels or medications.

Lip and Mouth Moisturisers

- Only ‘muco-adhesive’ water-soluble mouth moisturiser for lips and oral cavity should be used.

- Petroleum based moisturisers inflame open wounds and should not be used inside the mouth, particularly for those at high risk for aspiration

- Petroleum based lip moisturisers are contradicted during oxygen therapy

Other adjuncts to oral care

Protective mouth props (Open Wide® Mouth Prop) facilitate care in those who are unable to fully cooperate during oral hygiene.

- Made from dense foam, provides measure of safety for both patient and caregiver reducing injuries to the teeth, mouth or gums.

- Protective mouth prop essential for safe oral care in problematic patients such as those with Alzheimer’s, Dementia, strokes or spasticity issues who cannot keep their mouths fully open during oral care or might unexpectedly bite down during care.

- Requires training for use particularly in patients with resistive behaviour

Antibacterial Agents

The use of routine antibacterial mouthwashes has not been addressed in this article as differing opinions exist regarding routine use of Chlorhexidine versus other agents such as Cetylpyridium Chloride, 1.5% Hydrogen Peroxide, Thymol or GLLL. That being said, physician or dentist directed use of daily antibacterial agents should be included in patients’ plan of care. Whilst the use of antibacterial’s (i.e. low strength CHG gel) is advocated by many, staff must be aware that the use of any antiseptic or antibacterial agent does preclude proper mechanical debridement of tooth surfaces.

Recommendations for Best Practice Oral Hygiene Interventions in Long Term Settings

The need for diligent and more frequent oral – dental care is greater in those with dysphagia and must play a part in any aspiration pneumonia prevention programs.

Recommendations include:

- Change from tradition based practices to evidence based practices

- Demand 100% compliance with daily oral care practices

- Everyone is to be trained in evidence based practice to include oral assessment, oral hygiene care and caring for dentures

- Involve dentist, dental hygienist, oral health nurse as part of the healthcare team.

Summary:

As compliance plays a large part in oral care and patient outcomes, dentists should recommend products that facilitate oral cleansing and make it easier and more comfortable for patient and staff. To encourage the delivery of good oral hygiene it is essential to have all necessary tools and equipment readily at hand to foster frequent and standardised care. Use of a ‘timer’ during care should be encouraged to promote adherence to adequate brushing times.

Using informed, reasoned choices does drive healthcare objectives and shift providers away from “tradition based” practices.

Unfortunately talking about ‘best practice’ does not always guarantee the application and performance of best practice models. Without the development of on-going educational programs for nursing personnel and regular involvement by dental professionals, oral hygiene will continue to take a “back seat” in long-term care.